Sidney Paget By Courtesy of Goode Press and http://www.artintheblood.com [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

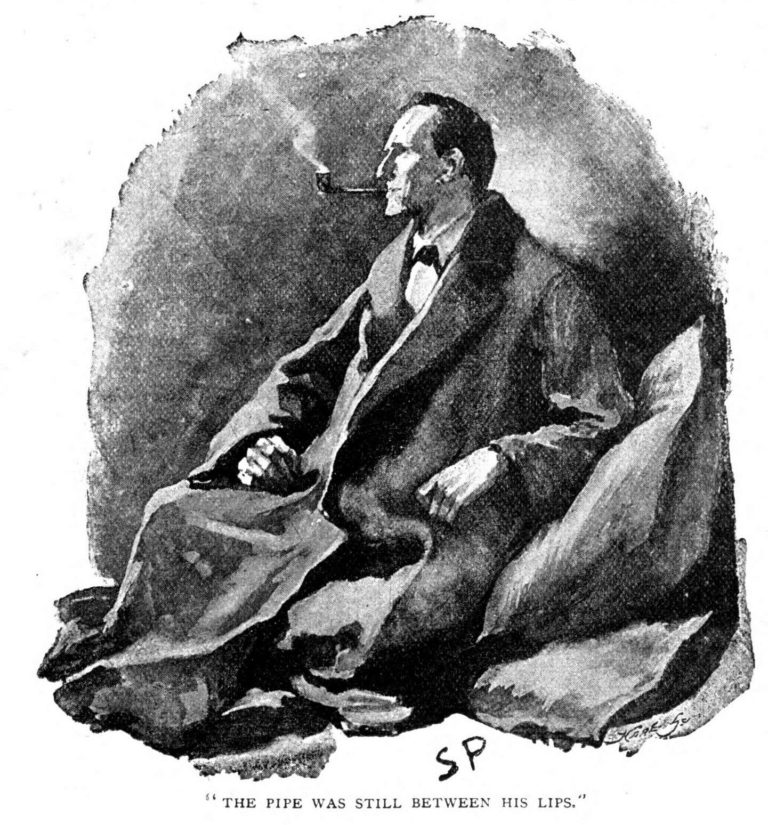

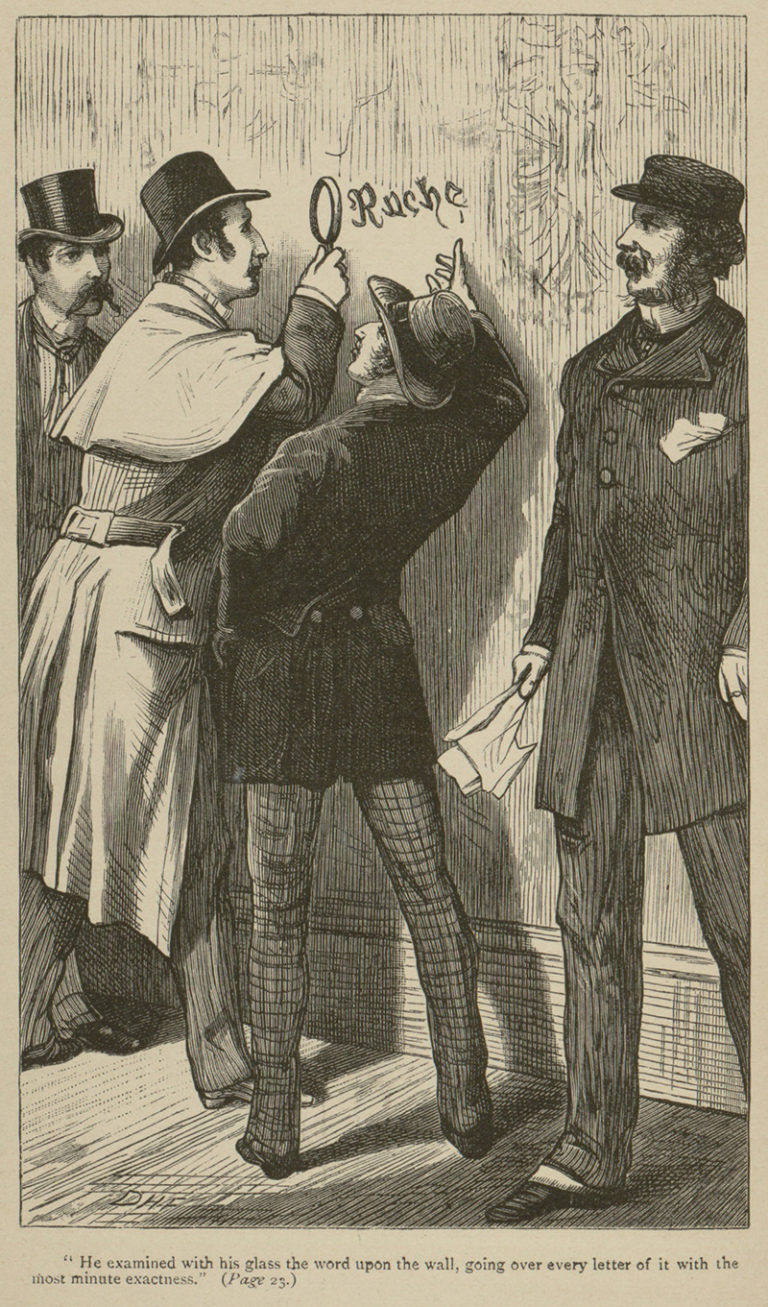

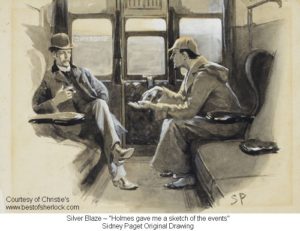

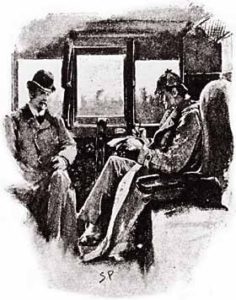

Figures (1) and (2) below are two different portraits by Sidney Paget of Sherlock Holmes. They both prominently display Sherlock’s pipe and the second one features a night coat while the first one, he is wearing a small tie. The character is depicted as clean-shaven with a pronounced nose. Figure (3) was drawn by D.H. Friston, another of Sherlock’s illustrators for the story, A Study in Scarlet (1887). This illustration depicts Holmes with a mustache, magnifying glass, top hat, and inverness cape. Figures (4) and (5) return to Sidney Paget as the illustrator. They show Sherlock wearing the deerstalker hat, inverness cape/coat and the mustache has moved to Dr. Watson. Comparing Figures (3) by D.H. Friston in 1887 to Sidney Paget’s figure (5) in 1891 from The Boscombe Valley Mystery story shows how the slight changes from mustache to clean-shaven, top hat to deerstalker hat, and coat to inverness cape took hold within a short period of time. These decisions by the illustrators on how to represent the character, Sherlock Holmes became part of the Holmes repertoire. Doyle’s original text and vision of the character first changed with their decisions on how to illustrate the stories for their respective magazines. These early decisions and illustrations continue to influence the Sherlock Holmes iconography.

![By Sidney Paget (1860-1908) (de.WP) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://shannonmckemie.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Sherlock_Holmes_Portrait_Paget.jpg)

Sherlock Holmes Portrait by Paget By Sidney Paget (1860-1908) (de.WP) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Figure (1)

Figure 2 Illustration by Sidney Paget

Source credit: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:Illus-twis-paget-08.jpg

Figure 3 D. H. Friston Illustration from A Study in Scarlet (1887)

Source credit: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:Illus-stud-1887-friston-01.jpg

Figure 4 Photo of original Sidney Paget drawing for Sherlock Holmes story “Silver Blaze,” with Holmes and Dr. Watson in a railway carriage. Captioned in The Strand Magazine as “Holmes gave me a sketch of the events” and offered at auction at Christie’s NY in June 2014.

Figure 5 Sidney Paget Source credit: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:Illus-bosc-paget-01.jpg

A British silent movie made in 1914 that has been lost is considered one of the early cinema adaptations. The British movie starred James Braginton as Sherlock Holmes. If you look at Figure (6) an image from the lost film shows Sherlock examining the body from the story, A Study in Scarlet (1887). This adaptation shows Holmes wearing the deerstalker hat and in a long distinctive coat. By (1914) the deerstalker hat and magnifying glass had become synonymous with the character, Sherlock Holmes.

Figure (6) 1914 British silent movie adaptation starring James Braginton as Sherlock Holmes Source credit: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:1914-stud-braginton-01.jpg

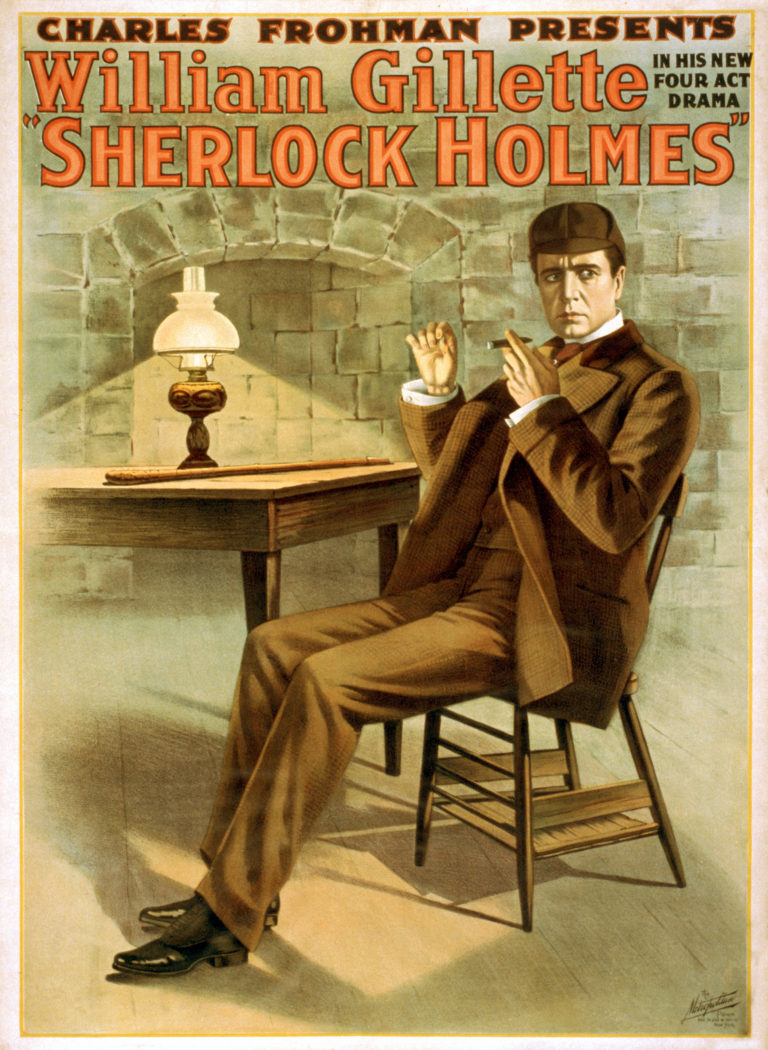

Figure (7) William Gillette See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The American cinema adaptation of the play was made in 1916 titled, Sherlock Holmes that had been lost to posterity until 2014 (The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia ). The restored Sherlock Holmes (1916) is now available for purchase by the general public. The plot of the adaptation revolves around the King of Bohemia, Irene Adler, and a photograph which primarily is taken from “A Scandal in Bohemia” (Schuttler 31). The desires to marry and is afraid that his former fiancée, Irene Adler, will use the photograph as blackmail. Adler outmaneuvers Sherlock and is able to maintain possession of the photograph. Irene provides assurance that she will not act against the King since she has found and fallen for a better man (Schuttler 31). Gillette modified the stories, names, and relationships in his play and cinema adaptation. The King of Bohemia became a “foreign prince” that employs Sherlock to retrieve the letters from a Miss Alice Faulkner, who is in possession of them. Sherlock pursues Professor Moriarty since he is the “Emperor of Crime” and is assisted by Billy, his servant (Schuttler 32). Gillette gives Holmes’s a love interest in Miss Alice Faulkner and a motivating factor of money for the letters (Schuttler 32). It closes with Holmes declaring his love for Alice. Gillette adaptation modifies Doyle’s signs.

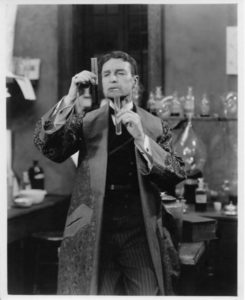

Figure 8 William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes (1916)

First, Gillette’s change to the character, Sherlock Holmes, to have his motivating factor in the adaptation to be money, doesn’t reflect Doyle’s Sherlock. Doyle’s motivation for the character, Sherlock Holmes through deduction and observation to solve crimes and bring criminals to justice is more for Sherlock’s enjoyment. In A Study in Scarlet (1887) Sherlock states to Watson: “…No man lives or has ever lived who has brought the same amount of study and of natural talent to the detection of crime which I have done. And what is the result? There is no crime to detect, or, at most, some bungling villainy with a motive so transparent that even a Scotland Yard official can see through it.” (Doyle 19) . With Sherlock motivated by money in the play and (1916) cinema adaptation, the character loses that enjoyment of the deduction and observation or the game in solving the crime. Additionally, Schuttler (1982) assesses in his article, William Gillette and Sherlock Holmes, the character falls in love with Miss Alice Faulkner. Although, in Gillette’s adaptation, Miss Alice Faulkner is substitutes for Irene Adler, whom Sherlock is fond of and is referenced across Sherlockian fandom as “the Woman,” this is a deviation because the character is shown to openly declare those feelings to Alice at the end (Doyle 187). Doyle’s Sherlock scorns the female gender and is not one to openly express those tender feelings as shown in the film. Watson narrates in The Scandal in Bohemia (1891) states, “To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman,” and “…It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise, but admirably balanced mind.” (Doyle 187) Doyle’s Sherlock would not open declare those emotions as Gillette shows Holmes on bended knee next to Alice before the film ends.

Second, Gillette’s representation of Doctor John Watson is non-existent. The character is introduced at the beginning as Sherlock Holmes’s confidant and arrives to the study in 221B Baker Street where Sherlock recommends that he reads a book. During Holmes’s adventures for Alice’s letters and with Moriarty and his gang, Watson is out off-screen. Watson returns at the end when Sherlock arrives at his doctor’s office and explains that he has invited Alice to come there. Watson remarks that Sherlock is in love. Instead of Watson assisting Sherlock during the case, Gillette created the minor character, Billy, as one of Sherlock’s servant who plays in what otherwise, would be deemed as Watson’s role assisting Sherlock.

Third, Gillette portrays Professor Moriarty as a bumbling criminal leader. The screen portrayal shows Moriarty planning two plots to foil Sherlock and in each of them; missteps happen where Moriarty is left with a gun without bullets and Sherlock outwitting his gang while rescuing Alice from Moriarty’s clutches. This Moriarty doesn’t seem to be Sherlock’s equal and the criminal organization feels small with the hand-full of people that are shown as under his direction. Doyle’s Professor Moriarty as spoken about by Sherlock in The Adventure of the Final Problem (1893) with a tinge of admiration spilling through the words, “..I beg, my dear Watson, that you will obey them to the letter, for you are now playing a double-handed game with me against the cleverest rogue and the most powerful syndicate of criminals in Europe.” (Doyle 562-563). The original Moriarty is a peer and equal to Sherlock’s intellect thus, as depicted in Gillette’s version; the character would realize that Sherlock would not fall for their ploys.

The fourth signs are: Sherlock’s hat, pipe, and cape. Gillette’s depiction of these items mirror Paget’s illustrations and the Victorian age of the stories. During the course of the film, Gillette as Sherlock Holmes is shown wearing various hats including the deerstalker hat and smoking the calabash pipe. The inverness cape is not shown and Sherlock wears either a formal night coat, suit jacket, or the night robe. The calabash pipe is shown and Sherlock makes a point during a scene that he’s not going to use another one but his own. The costumes otherwise, reflect the Victorian age.

Lastly, the fifth sign is Sherlock’s cocaine addiction. Gillette doesn’t allude or show Sherlock with an addiction other than, the character generally has a cigarette, cigar, or his pipe in most of the scenes.

Figures (7-9) show William Gillette as the character Sherlock Holmes from the 1916 movie. Figure (9) is one of the movie posters for the film. In Figure (7) Gillette is shown smoking from the calabash pipe and wearing a night coat. The movie poster in Figure (9) depicts Sherlock wearing the deerstalker hat but smoking a cigar rather than the calabash pipe. Also, for the poster the character is wearing a suit but does not have the inverness cape. Figure (8) shows Gillette as Sherlock working with his chemistry equipment in a long coat.

Figure (9)William Gillette

Source credit: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/images/b/bd/1899-sh-gillette-01.jpg

Works Cited

A Study in Scarlet. Dir. Edwin L. Marin. Perf. Reginald Owens. 1933. Film .

Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan. The Complete Sherlock Holmes Volume I . Barnes & Noble Classics , 2003. Print .

Leitch, Thomas. Film Adaptations and Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. John Hopkins University Press , 2007. Print.

Schuttler, George W. “William Gillette and Sherlock Holmes .” Journal of Popular Culture (Spring 1982): 31-41. web.

The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia . 2 January 2016. web. 25 August 2016.